A TENTATIVE ANALYSIS OF CRUDE OIL PRICE VARIATIONS OVER A 175

YEARS PERIOD

A.

After refining, crude oil is used mostly in four forms

1. Fuel for road, rail,

marine, and air transportation

2. Fuel for residential and

industrial heating

3. Raw material and fuel

for the petrochemical industry

4. Electricity generation

(used extensively for electricity generation in some regions; about 6% of

global oil production is used for that purpose overall)

B. Trade

Producers sell crude oil

physically to refiners, with which they are sometimes integrated, directly or

through traders, either for cash or through futures contracts or options. Part

of the production is stored for later release, either by producers or buyers,

or by governments, depending on market status. Production is currently about 90

million barrels per day (mmbbld) and, as an average, producers transfer to refiners a daily quantity

equal to one day of production.

C. Financial markets

In parallel with the

physical spot market where crude is sold for cash, there are important

financial markets, in the U.S., in London, in the Middle East and in Asia,

where financial instruments derived from physically traded crude oil are

exchanged, mostly as options or futures. The total volume traded daily is

between 20 and 40 days of production. There are two categories of traders in

these markets : those who produce and use crude

oil, and those who trade the derivatives with a financial purpose only. The

number of contracts traded in each category is more or less equivalent.

Some observers contend

that the trading of 20 to 40 days of production would lead to out-of-hand

speculation and market manipulation, but it seems that apart from some

short-term fluctuations, such is not the case, which numerous academic studies

seem to confirm by observation of significant price variations. In fact, all

that is produced once storage is full must be sold immediately to refiners for

eventual public consumption, at whatever price the market will bear, and the

total available intermediate storage capacity represents only a few days of

production. The only way to drive the price of the commodity up voluntarily is

to create a relative shortage by either reducing production and therefore

leaving the commodity in its production basin, or storing it somewhere between

production well and

consumer. The only party able to store all or part of crude oil

production in the long run is crude oil producers, in the production

reservoirs.

D. Physical storage

Crude oil can be stored

in various ways :

1. On land: in storage facilities,

above- or underground. World storage capacity is 45 days of production, 15 days

belonging to governments and 30 to private owners. In the U.S., where 2/3 of

the capacity belongs to the government, total capacity is 11 days of world

production. Other than governments, these facilities are controlled mostly by

producers and refiners. During the last 30 years, capacities have fluctuated by

only about 20%, which means that their flexibility is only about 10 days of

production.

2. At sea : global

capacity of marine crude oil carriers is about 20 days of production,

continuously on the move for the main part, but between 0 and 20% of that

capacity, according to market conditions, is on stand-by and can be used as

floating storage if needed, for up to 4 days of world production. This kind of

storage can be controlled by anyone with the wherewithal to do so.

3. In the underground

reservoirs whence crude oil is produced, each time production either slows down

or even stops, according to demand, as is often the case in the U.S. when

prices are low, sometime below production cost. Their known capacity is 19,100

days of production (52 years). Producers are the only party able to control

these reservoirs. They use them for storage, in an equivalent fashion, when

they sell future contracts or options, or when they try to create artificially

a general shortage in concert with other producers, a practice that has been

illegal in all democracies since the very early 20th century but is

tolerated of OPEC members.

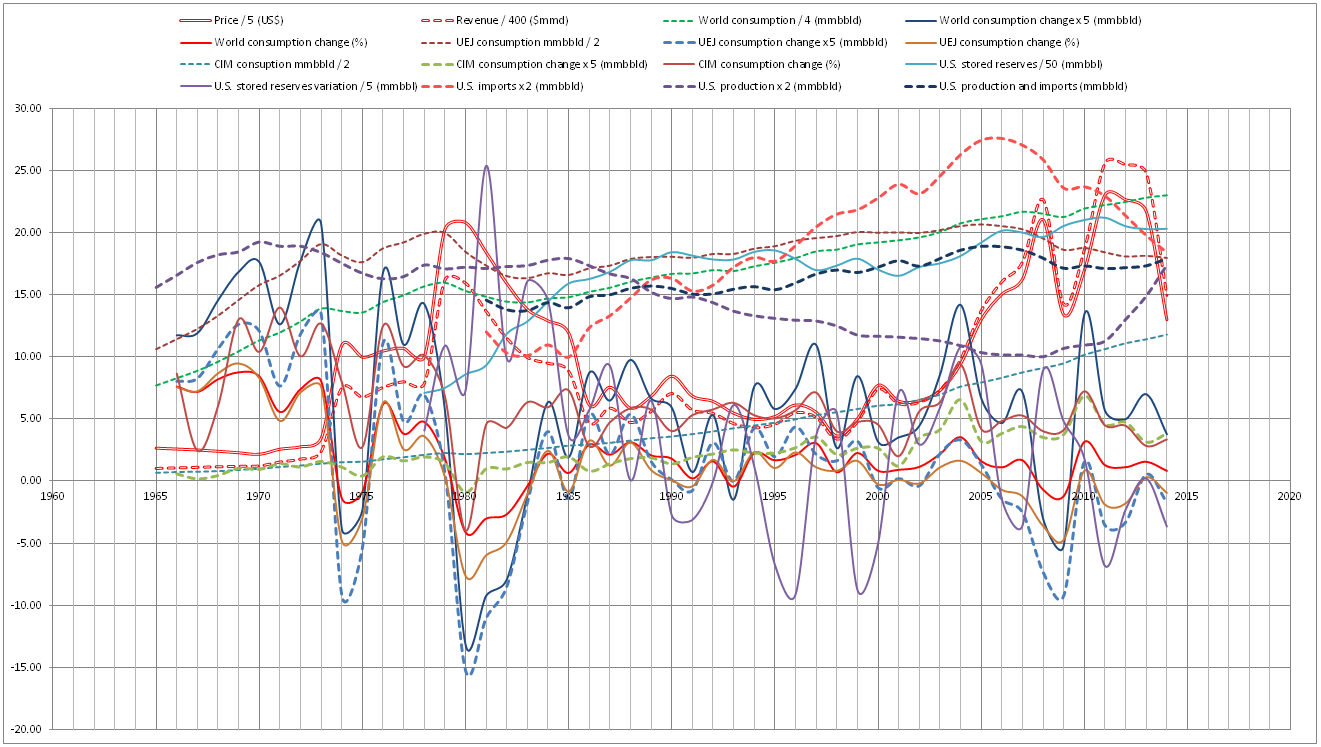

E. Crude oil consumption

since 1965

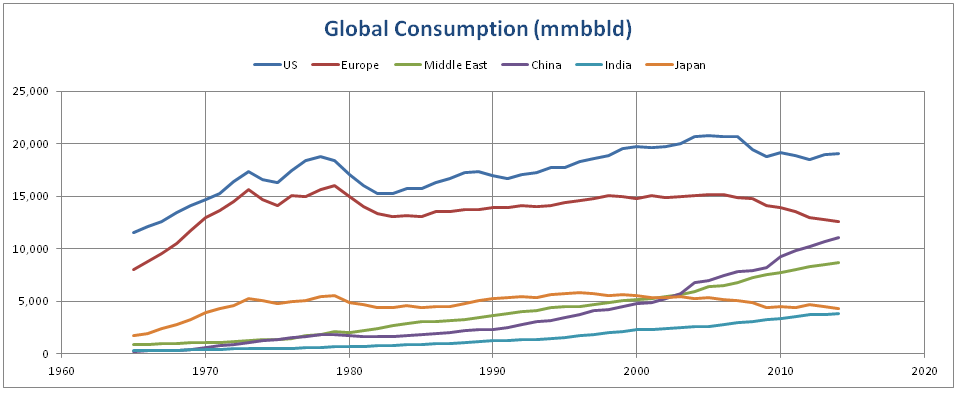

In the U.S., in Europe,

and in Japan (UEJ), consumption has been declining

for several years. In China, India, and in the Middle East (CIM),

consumption still increases, although economic indicators for China and India

hint that these countries’ growth is plateauing.

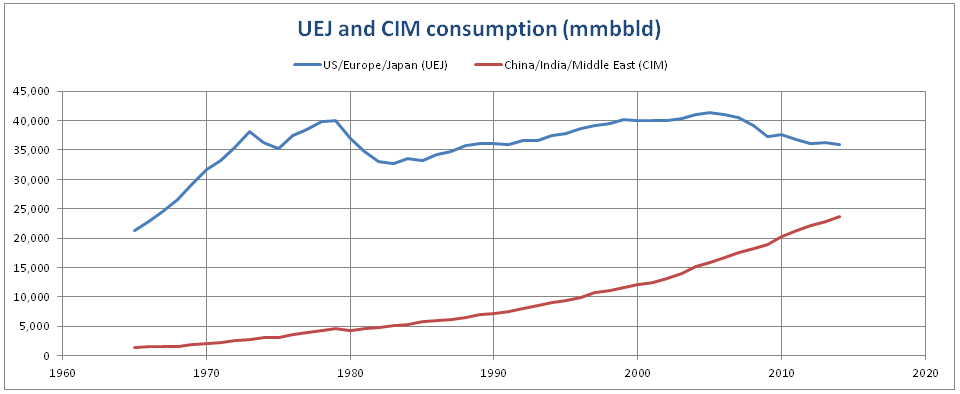

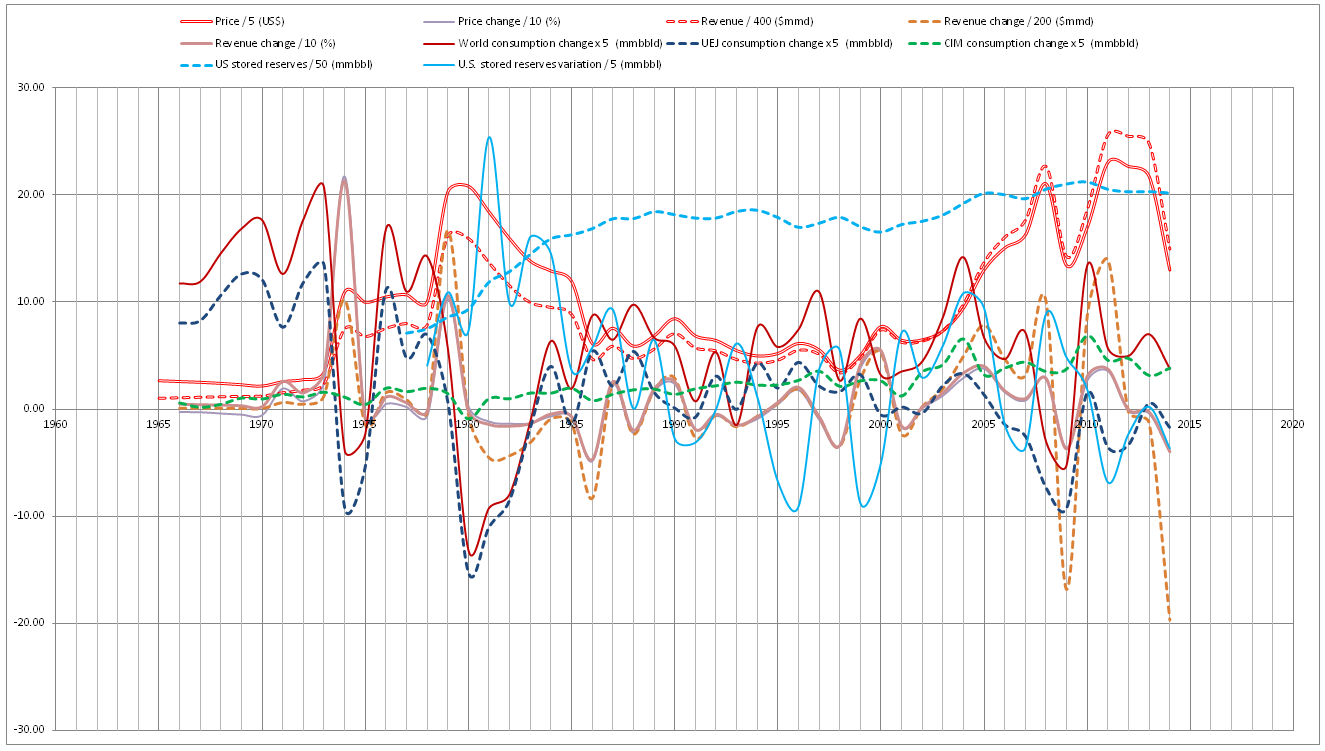

F. Comparing crude oil

prices since 1965 with changes in world consumption, changes in UEJ and CIM consumptions, and

U.S. stocks, as well as changes in U.S. stocks

Prices are year

averages, filtering out or dampening all short term variations. All prices are

in constant 2014 dollar. The only correlation, and not systematic at that, is

that UEJ consumption decreases when prices increase

steeply. CIM consumption is less affected. Changes in

U.S. stocks are either in correlation or in opposition with prices.

G.

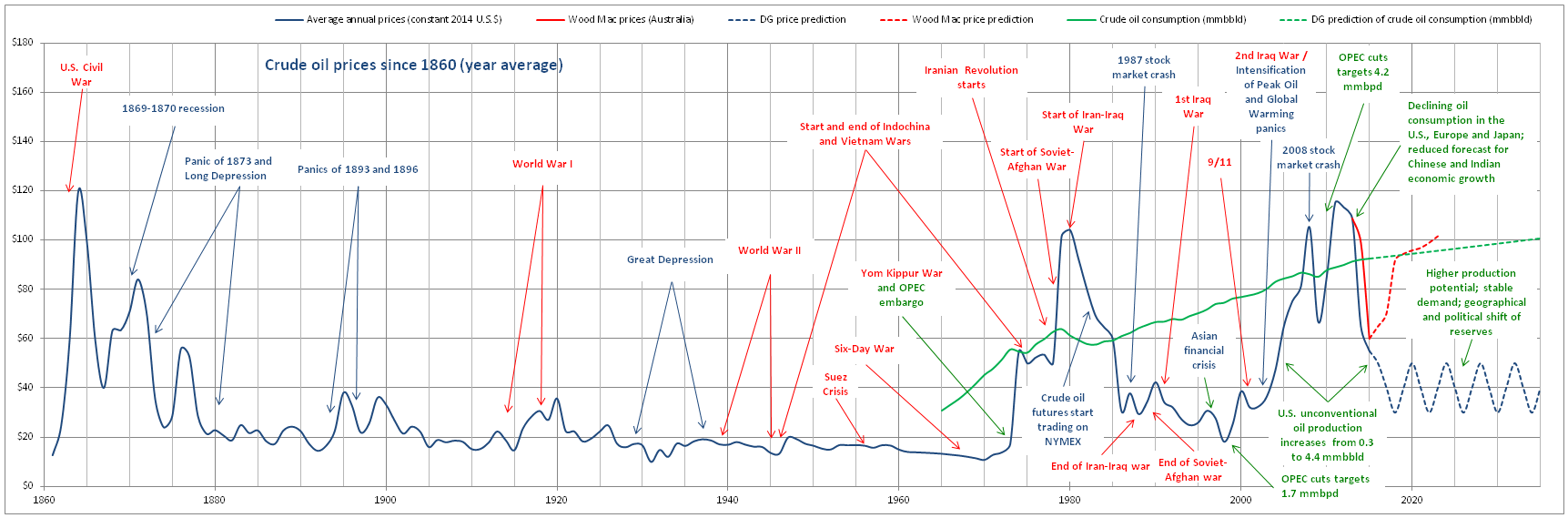

History of prices, 1860 to 2015, and probable future

Prices are year

averages, filtering out or dampening all short term variations.

H. Probable causes

Prices are year averages, filtering out or dampening all short

term variations. In particular, major unforeseen meteorological events, such as

hurricanes on the Eastern seaboard of the U.S. and in the Gulf of Mexico,

commonly result in a short term supply disruption that temporarily affects spot

prices, sometime greatly, but worldwide annual average prices only marginally.

Since the late 19th century, there have been only two

major periods of high prices: 1973 to 1986 and 2004 to 2014.

1. UP, 1973 to 1980: an embargo is imposed by Arab producers following the Yom Kippur War.

Prices increase from $17 to $55 in 1974, down to $50 in 1978 and up to $105

in 1980

2. DOWN, 1980 to 2004: in 1986 price is down to $31 and continues falling to $18

in 1998. It won’t be until 2004 that prices rise again above $50.

3. UP, 2004 to 2008: prices rise from $50 to $105

4. DOWN, 2008 to 2009: prices decrease to $67

5. UP, 2009 to 2014: prices increase up to $115

6. DOWN, 2014 to 2015: prices decrease to below $40 in August 2015

Historically, if the period from 1860

to 1880 is excluded as being pre-self propulsion age,

prices between 1880 and 2015 (135 years) were above $40 in constant 2014

dollars only for 23 years (17% of the time), in two periods of 13 and 10 years.

It seems that warfare and political

events are not necessarily synchronous with price variations, and neither is

U.S. storage capacity.

All three price increases were

triggered by deliberate efforts by Arab producers to manipulate markets through

production cuts.

After each of the first two

occurrences, market reacted by a drop of consumption. The first drop, from 1979

to 1983, was of 6 million barrels per day. A drop of 7.3 million barrels per

day occurred in the U.S., Europe, Japan region (UEJ)

but was dampened by the rise of Chinese, Indian, and Middle Eastern (CIM) consumption. From 2005 to 2015, the drop of UEJ consumption was 5.4 million barrels per day, again

dampened, and soon compensated, by an increase of CIM

consumption.

Additionally, the major event during

the second high price period was the development of U.S. unconventional

production and the synchronous decrease of U.S. imports. Between 2006 and 2015

U.S. production increased by 3.7 million barrels per day and imports decreased

by 4.6.

All price decreases were triggered by

a decrease of either global or UEJ consumption. The

2009 price increase saw the conjunction of the threat of a large production cut

and a temporary pause in the UEJ consumption

decrease.

Although price variations appear to be

sometime irrational in their amplitude, occasionally responding hyperbolically

to perhaps unreasonable fears, it seems that price variations respond

exclusively to supply and demand forces, influenced by political events only as

far as these induce OPEC producers to cut production drastically from time to

time. Each major price increase followed deliberate production cuts calculated

explicitly to manipulate the market. Each major price decrease followed

significant decreases in UEJ consumption, which

exceeded production cuts and were made possible mostly by efficiency

improvements. Furthermore, increasing U.S. production resulted in decreasing

imports. Some of the dips in consumption were no doubt due to production cuts,

but the 2009 threat of a 4.2 million barrels per day production cut was

followed by an actual worldwide 7 million barrels per day increase in

consumption, showing that either the threat had not been carried out, or

production cuts had found a substitute outside of OPEC.

This last circumstance was not lost on

Saudi Aramco when it decided not to proceed with production cuts as prices

started to tumble in July 2014.

Since the two steep price increases of

1973 and 2004 many things have changed in the oil market, which will no doubt

reflect on how prices vary in the future:

1. OPEC, and particularly Arab producers, do not control anymore a share of

production large enough to give them unilateral control of the supply side of

market

2. The U.S. is again the largest producer of crude oil, thanks partly to the

development of unconventional fields. The U.S. is also the largest producer of

natural gas and the second largest coal producer (behind China). Restrictions

on oil and gas exports have been eased by Congress.

3. The world’s largest reserve has shifted from Saudi Arabia to South

America

4. Consumption in the rich economies, particularly in the UEJ region, has not increased since 1973, mostly as a

consequence of technical innovation, and currently continues to decrease

5. Chinese and Indian consumption give signs of levelling out, a double

digit economic growth having become unsustainable in both countries

6. The “peak oil” scare seems to have been somewhat subdued after it was

recognized that despite increased global production, known reserves have

continuously increased in the last 35 years: in retrospect, and based on

current knowledge, it can be calculated that 1980 oil reserves were greatly

underestimated, at ¼ of what their assessment would be today.

I.

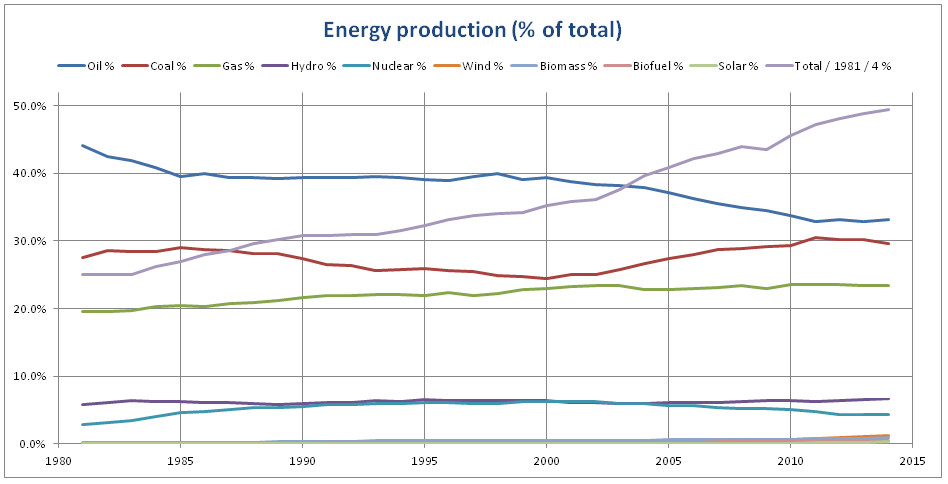

Coal and natural gas

Coal and

natural gas are the major energy sources for electricity generation but compete

with petroleum products as raw material for the chemical industry and as fuel

for heating purposes, either directly for natural gas or through co-generation

for coal in the developed world and directly elsewhere. Since 1981 global

energy consumption has increased by nearly 100% but the share of oil decreased

from 44% to 33% while coal’s share increased from 28% to 30% and natural gas

from 19% to 23%. Renewables increased from 0.1% to 2.5%. Since around 2000 oil

lost a 7% share while coal gained 6% and gas was flat at 23%.

Coal

is little used for automotive propulsion, the production of synthetic gasoline

being less than a quarter million barrels per day, and as regards natural gas

only between a half and a million barrel-equivalents per day is produced for

compressed natural gas vehicles, but all areas where oil competes with coal and

natural gas have a direct effect on global oil demand, and therefore price. It

so happens that since 2000 the relative productions of coal and oil have varied

in almost exactly opposite fashion, which can explain in part the unexpected

assistance volunteered by the oil and gas industry in support of the carbon

dioxide greenhouse effect theory, a theory that puts much more blame and odium

on coal than on oil and gas.

J.

The probable future

Based on

historical data and patterns, as well as relatively recent fundamental changes

in the crude oil market structure, it seems average annual oil prices in the

next few decades are likely to remain at the $40 average level, oscillating

between $30 and $50 a barrel, a level that is higher than during the past

periods of low prices because of higher production costs for unconventional

petroleum than for conventional. Any technological improvement leading to a

cost decrease of unconventional production will put downward pressure on global

oil prices.

It could be that

the only way to push oil (and natural gas) prices up in the long term would be

for concerted government action to put severe restrictions internationally on

global coal consumption. Although western governments endeavor to put such

restrictions into effect, it seems unlikely that Asian governments, Korea and

Japan apart, will follow suit just to please oil interests to the detriment of

the consumer and the economy, except of course if intense environmental

lobbying gained traction on these governments, an unlikely scenario for the

time being in those relatively poor countries (on a per capita basis), where

environmental worries, real or imaginary, will remain a luxury until everyone's

basic needs are satiated.

MMM

December 2014 – August 2015

December 2019

In the five years since this study was first written, it appears that prices oscillated between $37 and $74, remaining most

of the time between $40 and $60, rather than the predicted $30 to $50, a 25% divergence.